G for Gräfenberg – A rocky road to success

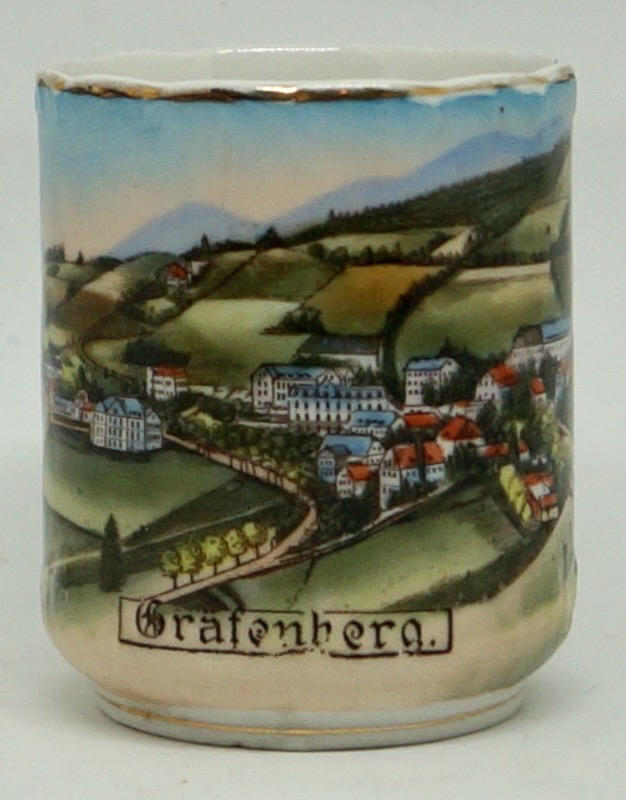

Since our topic is the “most pleasurable activity in the world”, as some say, and we therefore don’t always want to be deadly serious, we will entertain you today with a special piece from our collection: the cup depicted is 7 centimetres high and has “Gräfenberg” written on it. Only obstinate realists suspect a connection to the 4000-inhabitant village of Gräfenberg in Bavaria, first mentioned in records in 1172.

Since our topic is the “most pleasurable activity in the world”, as some say, and we therefore don’t always want to be deadly serious, we will entertain you today with a special piece from our collection: the cup depicted is 7 centimetres high and has “Gräfenberg” written on it. Only obstinate realists suspect a connection to the 4000-inhabitant village of Gräfenberg in Bavaria, first mentioned in records in 1172.

What seems much more plausible to us is instead that the word is a hidden reference to the achievements of the German physician Ernst Gräfenberg (1881–1957). Anyone smirking now has given themselves away! It’s true – in 1944, Gräfenberg described the “G-spot”, the erogenous zone in the vagina, which was named after him.

Joking aside: Ernst Gräfenberg is also of great importance due to his development of a contraceptive method, starting in 1928. It comprised a silk ring, or silver ring, wrapped in silver wire that is inserted into the uterus much like coils today. Previously, stem pessaries made of vulcanite or even metal had been used, which were not only extremely uncomfortable, but also a health hazard, because they very often led to injuries or ascending inflammation. It was therefore important “that the intrauterine ring really [lay] in the uterus and [did] not maintain any connection to the vagina, from which bacteria can ascend.”

Despite this crucial difference compared to previous developments, the Gräfenberg ring met with much disapproval, since “contraception was an ethically questionable issue in Germany.” The topic of “sterilisation and contraception” at the German Congress of Gynaecologists in 1931, for example, led to “lively and predominantly critical discussions”. Other sources speak of “far too little interest on the part of the medical profession in sexual counselling, and especially in the people’s desire for contraception.” [1]

A few years later – on 25th October 1935 in Munich – the German Society for Gynaecology even published an all-out renunciation of such contrivances: the use of intrauterine “means of protection” for the purpose of contraception was said to be harmful to the health and lives of German women. In fact, the so-called Third Reich forbade the production and use of intrauterine devices; the Jew Ernst Gräfenberg was still able to leave Germany and emigrate to the USA via Siberia and Japan.

It was only in the 1960s that Gräfenberg’s method was rehabilitated and became the precursor of more recent developments thanks to the two advantages it offered: on the one hand, as already mentioned, his contraceptive ring had no connection to the vagina and cervix; on the other hand, with his “principle of a change in form” – that is, flexibility during insertion – Gräfenberg had succeeded in taking a crucial step further than the rigid predecessor developments.

Today, the Gräfenberg ring is used only in China still (in modified form), but it paved the way for numerous subsequent developments. More on this on our coil wall at https://www.muvs.org/en/contraception/spirals/ and in our audio guide: https://www.muvs.org/en/museum/audioguide/die-spirale/.

Unless otherwise stated, the quotations come from: H. Ludwig, Verhütung der Empfängnis – Verhängnis der Verhütung – Die Leistungen Ernst Gräfenbergs und die Reaktion der Gynäkologie seiner Zeit, Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie105 (1983), 1197–1205

[1] Contribution by N. Goldberg to the discussion at the meeting of the Breslau Gynaecological Society on 18th February 1930, Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie1930, 23, 1447 ff.

Member of the Austrian Museum Association

Member of the Austrian Museum Association Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association

Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health

Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum

Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'

Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'