The silver lining of a difficult time

The average European household is home to around 10,000 objects; one actually means to have a clear-out, but never gets around to doing it. This has changed “thanks to” the coronavirus. During the lockdowns, quarantine and periods of working from home, many people decluttered their homes and came across various things that were too good to throw away. Lucky for us, because our museum has gained a total of eleven new objects as a result, two of which we would like to introduce to you today.

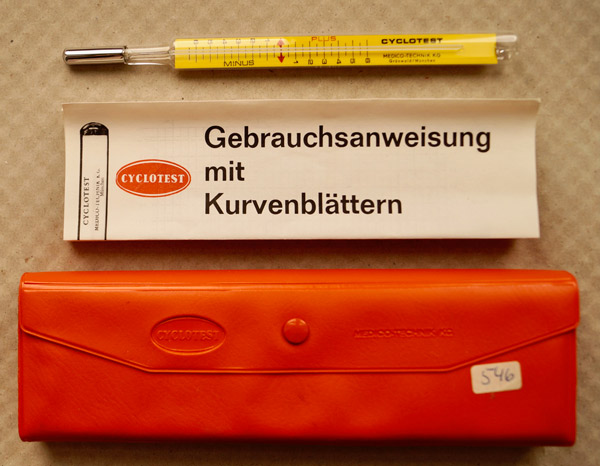

Cyclotest women’s thermometer: temperature measurement

The fact that only a few days of a woman’s monthly cycle are fertile has been known since the 1920s – thanks to the research of the Austrian gynaecologist and scientist Prof. Hermann Knaus and his Japanese colleague Kyusaku Ogino. One also knew, in theory, which days they were – the ones that fall exactly in the middle between menstrual bleeds. But the human body is susceptible to interference, and, so, predictions are never 100% reliable. Those who want to avoid getting pregnant at all costs, or those longing to now finally, finally fall pregnant, need more detailed information on top of counting days. Measuring one’s temperature in the morning is a suitable tool for this purpose, because when a woman is capable of reproduction, her temperature increases by a few tenths of a degree during ovulation.

As a method of contraception, temperature measurement is not very practical – because it requires a very regular cycle, a consistent daily routine, and an “iron will” for sexual abstinence on the “risky” days. The measurement must be carried out at the same time each day, between 6 am and 8 am, before breakfast, following at least 6 hours of undisturbed sleep, and always with the same thermometer, using the same measuring point (oral or rectal). Stress, colds or travel can affect the result.

For the Catholic Church, counting days and measuring one’s temperature are “permitted” methods. The Catholic Priest Wilhelm Hillebrand (1892–1959) from Rott (Germany) was one of the first proponents of this method: on 13th December 1935, he wrote that he had familiarised 17 women in his diocese with measuring their waking temperature so as to be sure of their infertile days, thereby justifying this manner of natural contraception.

Our new addition came complete with instructions for use, charts for entering the measured values, a storage case and even the envelope (postmarked 20th October 1980).

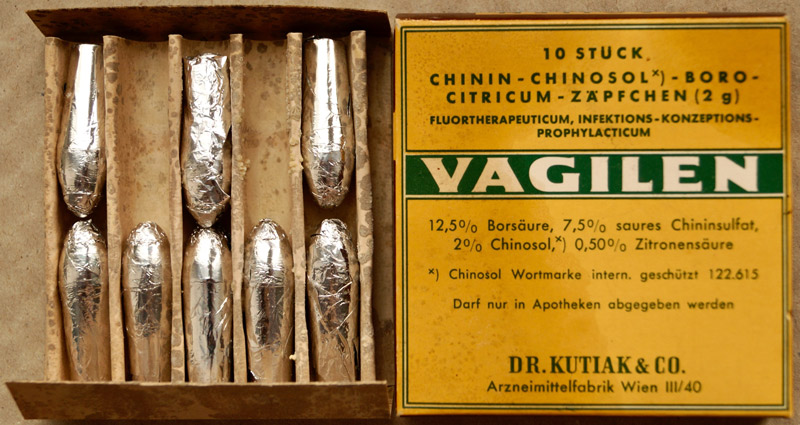

Vagilen vaginal suppositories: fluoro-therapeutic agent and contraceptive (1970)

These contain boric acid, citric acid, acidic quinine sulphate and Chinosol (potassium hydroxyquinoline sulphate), whose bacteriostatic effect was used to treat vaginal inflammation and discharge. It was also sold as a contraceptive and was on the market from around 1910 until 1974. During the Nazi era, its sale was prohibited, as for all contraceptives.

Prof. Tassilo Antoine (1895–1980), head of the First Women’s Clinic at the University Hospital in Vienna, gave a lecture in 1931, in which he stated: “Chemical contraceptives of this nature are not safe – if only because the proper technique of insertion is not so easy, especially if the woman has to do it herself. For, very often, the necessary intervening period between insertion and intercourse is not adhered to, which means that the agents have not yet dissolved. Despite their relative safety, the preparations made from cocoa butter or gelatin are often objected to by men because they make the vaginal canal unusually slippery, thereby reducing the sensation, and are also not exactly aesthetic in their use.”

Although we already have over 2,500 objects in our collection, of which around 320 are on display, we are always delighted to welcome new additions!

Cyclotest women’s thermometer: temperature measurement

The fact that only a few days of a woman’s monthly cycle are fertile has been known since the 1920s – thanks to the research of the Austrian gynaecologist and scientist Prof. Hermann Knaus and his Japanese colleague Kyusaku Ogino. One also knew, in theory, which days they were – the ones that fall exactly in the middle between menstrual bleeds. But the human body is susceptible to interference, and, so, predictions are never 100% reliable. Those who want to avoid getting pregnant at all costs, or those longing to now finally, finally fall pregnant, need more detailed information on top of counting days. Measuring one’s temperature in the morning is a suitable tool for this purpose, because when a woman is capable of reproduction, her temperature increases by a few tenths of a degree during ovulation.

As a method of contraception, temperature measurement is not very practical – because it requires a very regular cycle, a consistent daily routine, and an “iron will” for sexual abstinence on the “risky” days. The measurement must be carried out at the same time each day, between 6 am and 8 am, before breakfast, following at least 6 hours of undisturbed sleep, and always with the same thermometer, using the same measuring point (oral or rectal). Stress, colds or travel can affect the result.

For the Catholic Church, counting days and measuring one’s temperature are “permitted” methods. The Catholic Priest Wilhelm Hillebrand (1892–1959) from Rott (Germany) was one of the first proponents of this method: on 13th December 1935, he wrote that he had familiarised 17 women in his diocese with measuring their waking temperature so as to be sure of their infertile days, thereby justifying this manner of natural contraception.

Our new addition came complete with instructions for use, charts for entering the measured values, a storage case and even the envelope (postmarked 20th October 1980).

Vagilen vaginal suppositories: fluoro-therapeutic agent and contraceptive (1970)

These contain boric acid, citric acid, acidic quinine sulphate and Chinosol (potassium hydroxyquinoline sulphate), whose bacteriostatic effect was used to treat vaginal inflammation and discharge. It was also sold as a contraceptive and was on the market from around 1910 until 1974. During the Nazi era, its sale was prohibited, as for all contraceptives.

Prof. Tassilo Antoine (1895–1980), head of the First Women’s Clinic at the University Hospital in Vienna, gave a lecture in 1931, in which he stated: “Chemical contraceptives of this nature are not safe – if only because the proper technique of insertion is not so easy, especially if the woman has to do it herself. For, very often, the necessary intervening period between insertion and intercourse is not adhered to, which means that the agents have not yet dissolved. Despite their relative safety, the preparations made from cocoa butter or gelatin are often objected to by men because they make the vaginal canal unusually slippery, thereby reducing the sensation, and are also not exactly aesthetic in their use.”

Although we already have over 2,500 objects in our collection, of which around 320 are on display, we are always delighted to welcome new additions!

Member of the Austrian Museum Association

Member of the Austrian Museum Association Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association

Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health

Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum

Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'

Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'