How do you advertise the illicit?

The dark web – the hidden part of the internet – is said to provide a platform for communicating about the illicit – weapons, drugs, etc. But what was it like in the past if one wanted to market items or services that violated laws?

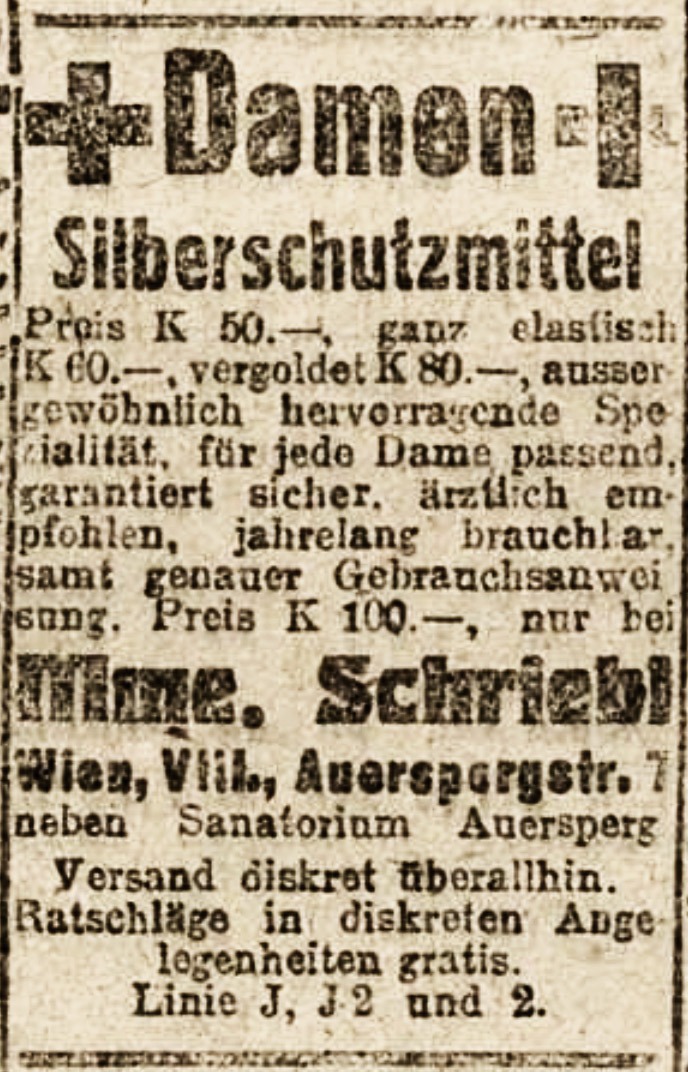

Neues Wiener Journal,

20.11.1919, p.9 (ONB/ANNO)

For this, there were advertisements in daily newspapers, which, seemingly harmless, in reality, contained codes or encrypted formulations that, though apparently beyond suspicion, contained telling turns of phrase for the initiated. These existed, for example, for contraceptives and abortions, which were considered immoral, obscene and criminal – and, in many countries, still are – or have once again been made – illegal.

If you scroll through newspapers from the beginning of the 20th century, you will find countless examples of advertisements – or ‘notices’ as they were called at the time – whose true subject matter would only be spotted by the expert eye.

We can take a look, for instance, at the Neues Wiener Journal from 1914: amongst the – presumably genuine – advertisements for piano tuners, dining room furnishings, bespoke tailoring and pawned lots are those for ‘safe and entirely harmless remedies for impairments’ and ‘genuine French remedies for ladies’ that boast ‘resounding success’. Naturally, they are dispatched in a ‘strictly discreet’ manner. ‘After just a few hours, you, too, will have relief’ – that is, the desired menstruation will set in. If the undesired condition had already progressed too far – in other words, there was an unwanted pregnancy, which needed to be terminated in secret – there are midwives or mediators who also offer their services – again, with strict discretion. One can then read, to take an example from the Salzburger Volksblatt from 11th October 1919: ‘Advice in discrete matters’ (‘Mme. Schriebl – Ladies’ Specialist). A certain ‘Mme. Wunderlich’ also had ‘advice in all discreet matters’ up her sleeve, according to her advertisement in the same newspaper from 8th November 1919.

By the way, the term ‘Madame’, which was frequently used in this context, was also a code term to signal a closeness to France: French people were considered to be expert in all aspects of love.

Doctors as helpers in times of need

Anyone who undertook forbidden procedures as a non-doctor and was clever enough would secure a partnership with a doctor and take advantage of this circumstance in their advertising. Yet, how could this be communicated? The 1919 advertisement of ‘Mme. Schriebl – Ladies’ specialist’, who sold a ‘silver protection method’ – an ‘extraordinary specialty, suitable for every lady’, (1) was genius in this regard. The goods in question were silver cervical caps for contraception. She also gave ‘advice on discreet matters’ if necessary. What was meant by this was clear to the readers. The address she provides is also telling: Vienna VIII, Auerspergstrasse 7, next to Auersperg Sanatorium. (2) The Auersperg sanatorium, originally established as a private sanatorium for the treatment of skin and venereal diseases and converted into a general sanatorium in 1910, performed abortions in ‘medically justified cases’. The ‘medical justification’ was often acquired with hard cash. It is hard to believe that the Mme. Schriebl in question provided her service in ‘discreet matters’ without the neighbouring institution knowing. One can more likely assume that this close proximity provided a kind of medical safety net for her, to which she made reference in her advertisements.

Having no money increased the risk

The term ‘ladies’, used in the listings, is also to be understood as code: it signals that the ‘assistance’ costs money, for the risk was high. Only women of society had money though. In defence of the providers, it must be said that they often adapted their fees to the means of their customers – Marie Baschtarz, for example, who offered her services as ‘Madame Mittermayer’ in the Vienna suburbs, charged between 15 and 200 krone. By comparison, the rent for the apartment in which the abortions were carried out was 60 krone per month.

Those who could not afford the fee of a professional service, such as women of a lower social status, or even maids, etc., or those who could not access information, were instead dependent on underground rumours and hearsay. As can be seen from the records of court proceedings, public transport was well suited for this. One could easily get into conversation there and would hear of names, aids and appliances, possible ways…

At the beginning of the 20th century, doctors largely kept out of the topics of contraception and abortion, because they were said to not be medical tasks. The procedures were therefore carried out either by the women themselves or by (former) midwives, or at least people with basic medical knowledge – once even by a butcher. The do-it-yourself methods were mostly primitive; the risk of serious damage to health, or even death, was high. This was different when midwives or other experienced persons got to work, as shown by the statements of ‘Mme. Mittermayer’: “After guidance with the uterine speculum, an ordinary rubber catheter would be inserted into the uterus of the woman concerned, who would be asked to lie down on the divan for this purpose. I always then fixed the catheter in place with a cotton-wool pad.” Even the prominent coroner Prof. Albin Haberda paid tribute: “None of the women has become seriously ill; the level of caution extended as far as giving in-house haemostatic agents to be taken away for external cases...”(3) In an emergency, she would even have been able to get the help of a doctor with whom she was friendly.

‘Mme. Mittermayer’ had acquired over 100 customers from all over the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy within 15 months thanks to her listings.

1) For example Salzburger Volksblatt 19.11.1919, p. 9, and Wr. Caricaturen 1.10.1919.

2) Neues Wiener Journal 20.11.1919, p. 9

3) Katharina Riese: In wessen Garten wächst die Leibesfrucht?, 1983

Member of the Austrian Museum Association

Member of the Austrian Museum Association Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association

Seal of Approval of the Austrian Museum Association Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health

Supported by European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum

Nominated for the EMYA Museum of the Year Award 2010. First Winner of the Kenneth Hudson Award given by the Trustees of the European Museum Forum Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'

Accepted into the 'Excellence Club - The Best in Heritage'