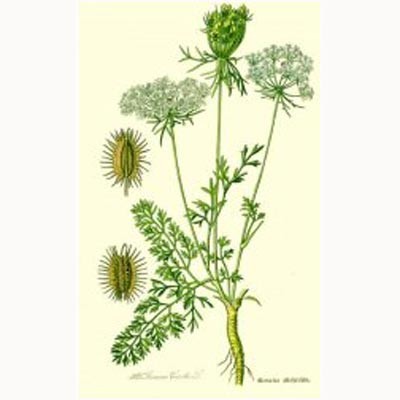

Wild Carrot

Hobby gardeners and nature lovers look forward to seeing this biennial plant with the tender umbels and long, pinnate bracts that resemble fine lace. This gave the plant one of its names, Queen Anne’s Lace: according to legend, Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665-1714) pricked her finger and blood dripped onto the white lace collar she was sewing at the time.

In the 1970s, the wild carrot could be found in nearly every meadow. As a result of overfertilization and excessive mowing, the frequency of its appearance has been greatly reduced, and the plant has completely disappeared from some areas. Once considered a noxious weed, the wild carrot is currently being planted for decorative reasons. For many insects, the wild carrot represents an important food source, because it blooms for several weeks in the summer and provides an abundance of pollen and nectar.

The roots are edible, but woody and hard when mature. In the spring, the young leaves can be used for salads. Because of its high sugar content, the root was used by some cultures to sweeten puddings and other dishes.

The wild carrot closely resembles the poison hemlock, and physical contact can cause phytophotodermatitis or contact dermatitis in individuals with allergies.

Its seeds are used for medical purposes. When the plant’s brown and dry, the stem’s cut several centimetres below the flower head, which are then rubbed together until the seeds fall out. They’re rinsed in water, dried, and stored in an airtight container.

The plant contains a number of pharmacological agents that are ascribed the following effects, among many others: analgesic, antiarthritic, antidepressant, antipsychotic, antischizophrenic, antidotal, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic, antiestrogen, antihistamine, antioxidant, antiseptic, anticonvulsant, antiepileptic, anxiolytic, antistress, anti-PMS, anti-hangover, antiviral, anticancerous, expectorant, fungistatic, immunostimulating, as an MAO inhibitor, sedative, tranquilizing, aphrodisiac and stimulation of pituitary gland.

When used as a contraceptive, the seeds are ground or brewed as a tea and taken for several days when having unprotected sex. When larger doses are taken as a contraceptive after having sex, they are assumed to prevent a pregnancy. In contrast to the morning-after pill, these seeds don’t block fertilisation of the egg, rather they prevent the fertilised egg from attaching to the uterus wall.

Sources:

John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, 1997

John M. Riddle, Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance, 1992

Helga Dietrich and Birgitt Hellmann, Vom Nimbaum bis zur Pille, 2006