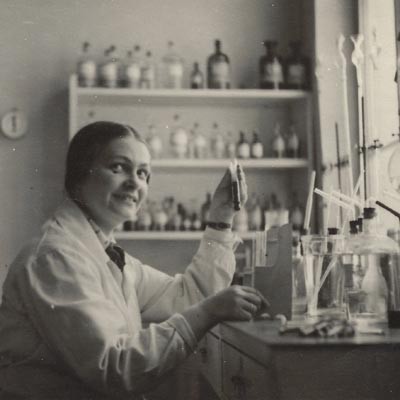

Regine Kapeller-Adler (1900-1991)

“A significant achievement for gynaecology and obstetrics” is what “Der Wiener Tag” [The Viennese Day] in May 1933 called the new pregnancy test that had a few hours previously been presented at the Viennese Biological Society. This test was developed by a woman – a rare exception amidst all the male inventors: the chemist Dr. Regine Kapeller-Adler, assistant at the Institute for Medical Chemistry at the University of Vienna. She developed a detection method for the amino acid histidine, which had first been discovered in 1896.

“The speaker had first refined a chemical colour test so that it became possible to identify a specific body, so-called histidine. Studies revealed that it is precisely this histidine that is abundantly excreted in the urine of pregnant women.” While urine containing histidine stains red to dark red, histidine-free urine turns an intense yellow (with a green tinge) to brown.

“The speaker had first refined a chemical colour test so that it became possible to identify a specific body, so-called histidine. Studies revealed that it is precisely this histidine that is abundantly excreted in the urine of pregnant women.” While urine containing histidine stains red to dark red, histidine-free urine turns an intense yellow (with a green tinge) to brown.

Kapeller-Adler’s new method was notable for two reasons: firstly, because of its speed. “The great advantage of this new chemical pregnancy test lies in the fact that it can be carried out in four hours, whereas the tool that has been most ideal for early diagnostics up until now [...] requires a hundred hours until it can be read.”

The second advantage was the introduction of a chemical instead of a biological reaction: the conventional method up until that point, the Zondek-Aschheim method, required young female mice, who had to lose their lives in order for the result to be read.

Since Kapeller-Adler’s academic work addressed medical questions, she embarked on a medical degree in 1934, though for political reasons she was no longer allowed to take the final viva in March 1938. As a Jew, she also lost her post of employment, and before that she had also been denied her postdoctoralqualification– as a woman and a Jew.

Her husband, Ernst Adler, was also persecuted and tormented for racist reasons and only just escaped deportation to the Dachau concentration camp.

The development of the pregnancy test proved to be a life-saver for her family: the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh offered her a post at what was the first, and at that time only, Pregnancy Diagnosis Laboratory in Great Britain. From there, she continued her academic career and gained recognition, grants and awards. In June 1973, she was presented with the University of Vienna’s Golden Honorary Diploma.

Kapeller-Adler’s method was an important step towards the modern pregnancy test, but not yet the final breakthrough. It in fact took until the end of the 1950s until the tests using animals could be done away with. Even the immunological pregnancy tests developed at that time were not yet perfect and were gradually improved.

The life and work of Regine Kapeller-Adler were showcased in the exhibition The Medical Faculty of Vienna 1938 to 1945 at the Josephinum in Vienna (2018).