“... ’cos tut-tutting aggression’s always the worst...“

“Everyone knows these days the customary connections between sex life and human life, in that the one is generally said to come about because somebody did the other, a quasi-causation connection”. (page 154)

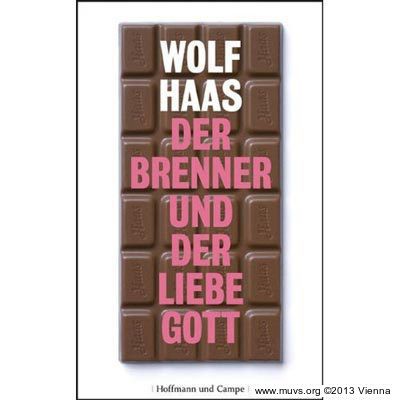

Since, apparently, not everybody is familiar with that “causation connection”, the setting for the latest crime novel by acclaimed Austrian writer Wolf Haas, “Brenner and God”, is a Vienna abortion clinic. Readers will immediately be able to tell that Haas has done his research, both in and outside the clinic on Fleischmarkt in central Vienna.

The woman director of the clinic, Doctor Kressdorf, is being harassed by Sebastian Knoll, the head of a Pro-life organization, using every possible means: “…loads of problems recently with bigots in front of the building, demonstrators like. They’re against abortions ’cos they reckon it’s wrong, a million reasons, God, the Virgin Mary yadda yadda yadda…”.

“… the pro-lifers had gradually bought up the flats round the building where the clinic was, and of course, big questions about where they got all that money. And since ownership of the majority of the property in the building pro-life, everything possible to try to stop the clinic’s lease, power cuts got more frequent… “ (page 17)

Since in Austria there is no legal protection of buffer zones around abortion clinics “the protesters form a guard of honour in front of the clinic” and harass staff and patients. The clinic resorts to protecting itself: “you’ve got to picture it: to the right of the door is an anti-abortionist proffering a wreath made of roses with a picture of an embryo and to the left of it stands a bull-necked woman with a shaved head from security, a quasi intimidation equilibrium”. (page 17)

When Doctor Kressdorf’s two-year old daughter is kidnapped, Knoll is immediately suspected of being behind it, “once in an argument [he’d] told the doctor she should take good care of her own child … so God would not make her child disappear like all the children she’d stolen away from God.” (page 52)

But they can’t pin anything on him: “Of course, Knoll hadn’t stood on the street himself and personally prevented patients from entering the clinic. You don’t do that sort of thing yourself! Knoll had enough bigots to stand all day by the entrance with a rapt expression, holding up the photo of the embryo emblazoned with the word ‘MURDER’.” (page 51)

In the course of the kidnapping investigation the police find hidden cameras that Knoll had been using to spy on events in the clinic and collect material that he could use for leverage (page 92). We won’t give away any more of the story here, but fans of Wolf Haas will be able to draw their own conclusions.

Haas has done his research carefully and describes the beleaguered situation of the clinic in accurate detail. There’s only one factual error, which isn’t relevant to the storyline but should be pointed out so that readers aren’t left with a false impression: the time window for the term-limit option does not apply to minors. A late abortion in a young person is therefore not illegal and consequently wouldn’t provide grounds for blackmail. It is unlikely that Doctor Kressdorf would not have known that.

Note: Brenner and God has not yet been published in English: page numbers given here refer to the German edition.

Wolf Haas: Brenner and God. Hoffmann und Campe, 2009. ISBN 978-3-455-40189-9